We present a interview with Htet Khine Soe, an activist who organized in Burma1 for more than 20 years before relocating to Mae Sot in Thailand at the end of 2021. The interview was carried out by Ban Ge, a Chinese anarchist who has come back and forth to Mae Sot and worked closely with Burmese activists after the coup.

Preface

This February, the military coup in Burma entered its fifth year. In Yangon, life appears to have returned to a fragile normality. Worn down by a revolution that seemed endlessly prolonged with no clear horizon of victory, many who once left their jobs to join the Civil Disobedience Movement have gradually returned to the system they once abandoned.

Meanwhile, in rural areas and border regions controlled by the armed forces of the resistance, the “Spring Revolution” has increasingly hardened into a stalemated civil war. The military junta’s drone strikes and aerial bombardments have become routine, and civilians continue to pay the price.

Under these conditions, the military has moved forward with what it calls a long-delayed general election—widely described by observers as a sham election. With opposition parties dissolved or suppressed, there is little doubt that the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) will secure victory.

Shortly after the 2021 coup, the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM)2 and nonviolent protests met with brutal military crackdowns. Some activists fled to the jungles, where they trained with ethnic armed organizations that had long fought against the military, forming People’s Defense Forces (PDF) and launching armed resistance. Others embarked on exile, scattering across the world. Mae Sot, the Thai border town opposite Burma, became one of the first destinations for many exiles and wounded resistance fighters.

In February 2023, during events marking the second anniversary of the coup, I met Htet Khine Soe (Ko Htet), a Burmese anarchist activist, and decided to follow him to Mae Sot. We took an eight-hour bus ride from Chiang Mai, crossing the mountain ranges of Thailand’s Tak Province before reaching the border. Along the way, I told him about anarchist self-organized spaces and resistance networks in China. He, in turn, recounted stories from the revolution—flashmob strikes, urban guerrilla actions, assassinations, escapes, and exile.

During the first year after the coup, Ko Htet helped organize the General Strike Committee and flash mob strikes, and eventually became drawn into urban guerrilla operations. After a comrade he worked closely with was arrested, his name appeared on the wanted list and was circulated on a state-run media platform, forcing him to flee Yangon.

In December, he escaped to Lay Kay Kaw, a town in Karen State, then known among young exiles as a “liberated area.” With PDF training camps located in nearby jungles, the town became a hub through which weapons and ammunition circulated, eventually making their way back into cities like Yangon and Mandalay to supply urban guerrilla groups.

But this also made Lay Kay Kaw a military target. On December 15, five days after Ko Htet arrived, the military launched airstrikes on what had been called a “peace town.” He fled across the river into Thailand alongside waves of other displaced young exiles.

His wife, Su Yi, an activist too, later arrived in Mae Sot with their two children to join him. The family obtained “stateless cards” and finally settled here. Their home gradually became a gathering place for the revolutionary exile community. After October 7, 2023, their children—an elementary-school-aged son and daughter—would tell visiting guests who brought Coca-Cola, “Don’t drink Coca-Cola—for Palestine.”

In 2025, Ko Htet and Su Yi opened a T-shirt shop in Mae Sot called All Colours Are Beautiful—an anarchist wordplay hinting at the slogan All Cops Are Bastards (ACAB). Upstairs from the shop is their screen-printing workshop, where they produce many of the shirts sold there. One of the most popular designs reads in English, No One Is Illegal. In a town where much of the population lives in various shades of legal uncertainty, wearing that shirt in public is strikingly provocative. Recently, Ko Htet sent me a photo of an immigration detention registration card showing a Burmese detainee standing before a height chart—the standard mugshot background—still wearing that same No One Is Illegal shirt.

On the fifth anniversary of the coup, I invited Ko Htet to reflect on the revolution from an anarchist perspective: the tensions between their movement and the mainstream revolutionary forces represented by Aung San Suu Kyi, and how leftist networks of Burma—formed before the coup—have continued to organize and survive through exile.

Htet Khine Soe in a flash mob strike in Yangon, March 2021.

I. The Streets

After the 2021 coup, how did anarchists in Burma mobilize within the anti-junta movement? And what were your main disagreements with mainstream supporters of Aung San Suu Kyi?

On the eve of the coup, rumors were already circulating, but almost nobody truly believed it would happen. The 2008 Constitution3 had already granted the military enormous institutional power, including an automatic 25% of seats in parliament. Under such arrangements, it seemed unnecessary for the military to seize power outright. Yet, on February 1, 2021, the coup took place.

On the morning of the coup, I discussed with comrades who used to work with the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU)—one of the country’s main leftist student organizations—and with members of our anarchist antifa group how to mobilize people to take to the streets. However, senior figures of the National League for Democracy (NLD) who had not yet been arrested, along with supporters of [Burmese politician] Aung San Suu Kyi, called on the public not to act immediately and instead to wait seventy-two hours. They were spreading the belief that international aid—and even an R2P intervention4—would soon arrive, encouraging people to stay home rather than take to the streets in protest.

But that same day, the internet was cut off. Suddenly neither the military nor the NLD could effectively spread their propaganda. The movement I was involved in struggled to bring people onto the streets during the first three days. Communication between us was difficult, and organizing under those conditions was extremely challenging.

The female workers of the Garment factory in Yangon’s well-known industrial district of Hlaingthaya were among the first to take to the streets in protest, while ABFSU, ignoring the NLD leadership’s calls for restraint, began organizing on their own. Meanwhile, ordinary people started spontaneously banging pots and pans from their balconies every evening in protest.5

February 6 was the first, biggest day. Garment workers in Hlaingthaya again took to the streets while the military quickly blocked the roads. But on that same day, a nationwide wave of demonstrations began. Even people I knew who were normally indifferent to politics joined the mass protests.

At that moment, nearly everyone united under the same slogan: opposing the coup and demanding the release of Aung San Suu Kyi. I even responded to NLD calls by buying red clothing and wearing it to demonstrations.

On February 12, I became involved in organizing the General Strike Committee (GSC), which was formed for the fight against dictatorship from the people’s movement, made out of party members from a total of 25 groups, including ABFSU, labor organizations, and political parties. The GSC’s core demands were resisting military dictatorship, freeing Aung San Suu Kyi and all political prisoners, and abolishing the 2008 Constitution altogether. At that time, any political mobilization that did not include the demand to release Suu Kyi would struggle to gain public support. Still, we always emphasized the release of all political prisoners, not only her.

Our main disagreement with the NLD concerned the 2008 Constitution. NLD leaders and their supporters hoped to use the 2008 Constitution as a framework to restrain the military and preserve the outcome of the election. We, on the other hand, believed that this era had ended and that the constitution itself must be abolished. People needed to unite not just to defend an election result, but to dismantle the military’s structural role in Burma’s political system.

At that time, protests took place almost daily. Public enthusiasm for resisting military rule was overwhelming. Whether or not people fully agreed with our political positions, once a crowd gathered, more people kept joining. During demonstrations, we organized speeches and morale-boosting segments explaining why removing the 2008 constitution was necessary.

On March 3, during a protest organized by the General Strike Committee, more than three hundred people were arrested. After that, some groups began making crude explosive devices and noise bombs to push back against police and military repression in the streets. At the same time, the NLD and its supporters began accusing us of resorting to violence. They argued that once protests became violent, the revolution’s image in the international community would suffer.

On social media, NLD supporters also labeled the General Strike Committee as communist or leftists. Because of decades of state propaganda portraying communism as a national threat, such accusations easily created suspicion and hostility toward us among the public.

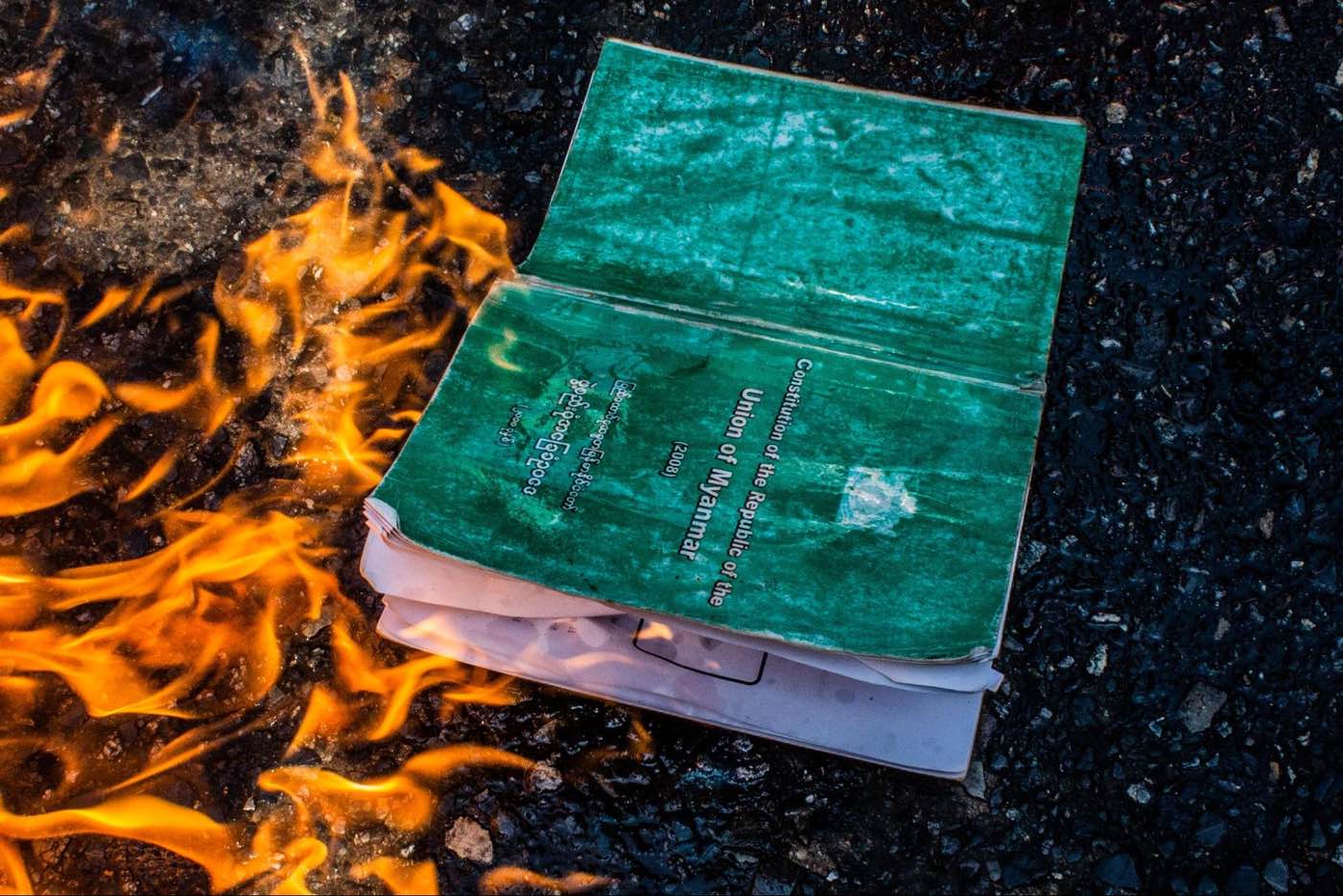

March 27, 2021, “Anti-Fascist Day”: leftist groups burning the 2008 Constitution on the street in Yangon. (Photo: Mar Naw)

March 27, 2021, “Anti-Fascist Day.” Leftist groups burning the 2008 Constitution on the street in Yangon. (Photo: Mar Naw)

After the military’s bloody crackdown on March 27, large-scale peaceful protests in the cities became almost impossible, and many people went to the jungles to begin armed resistance. But some chose to stay and continue the struggle in urban areas. Could you describe what that period was like?

March 27 was Burma’s Armed Forces Day, known locally as Tatmadaw Day. That day, large anti-coup protests once again broke out in major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay, and we took part as well. The military responded with brutal force, killing hundreds of protesters across the country.

It is important to understand the historical meaning of that date. March 27 was once known as Anti-Fascist Resistance Day (ဖက်ဆစ်တော်လှန်ရေးနေ့)and was only renamed Tatmadaw Day in 1955. Originally, it commemorated the birth of the very army that later staged the coup: on March 27, 1945, General Aung San led Burmese forces in an uprising against Japanese fascist occupation. After Burma gained independence in 1948, Aung San’s Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League became the ruling political force.

So on that same commemorative day in 2021, people took to the streets to protest against the coup carried out by that army, effectively reclaiming and redefining the meaning of the day through resistance. The massacre that followed demonstrated once again that the force once celebrated as anti-fascist had itself become fascist. After the crackdown, many of us deliberately began referring to March 27 once again as Anti-Fascist Day.

Another day we have tried to reclaim is Martyrs’ Day on July 19, which commemorates the assassination of General Aung San. In official narratives, only ethnic Bamar figures are recognized as martyrs. Leaders from minority ethnic groups who died in conflicts with the central state are rarely, if ever, granted that status.

After the March 27 crackdown, it became increasingly difficult to organize peaceful demonstrations in cities. Many of my comrades left for the jungle to receive military training with ethnic armed organizations. Some went to Kachin State along the China-Burma border and Rakhine State bordering Bangladesh to train with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and Arakan Army (AA), while others went to the Karen State border region to join the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA).

Later, some who returned from those areas told us that when new arrivals reached the camps, they were often greeted with a simple question as a test: “Are you joining the revolution to liberate the people, or just to free Aung San Suu Kyi?”

As for me, I chose to remain in Yangon. From that time on, together with other comrades, we began organizing flash mob strikes—brief, rapidly assembled demonstrations that dispersed before security forces could respond. Many young people enthusiastically joined these actions, allowing resistance in the city to continue, even under increasingly dangerous conditions.

March 27, 2021, a flash mob protest in Kyi Myin Daing, Yangon. The banner says, “We will throw the fascists’ bones into the Bar Ka Yar ravine.” In Kyi Myin Daing, there is a large ravine called Bar Ka Yar. The flag in the photo is ABFSU flag. (Photo: Mar Naw)

How did strategies change for those who stayed in Yangon compared with the earlier phase of resistance?

Flash mob strikes continued in Yangon until the end of 2021. During this period, our demands were no longer limited to opposing military rule or calling for Aung San Suu Kyi’s release. Instead, we began using protests to communicate broader political messages and bring forward issues that mattered to us.

As mentioned before, we worked to reinterpret historical commemorations such as Anti-Fascist Day and Martyrs’ Day. We also pushed discussions about gender issues within the revolution, the impact of mining projects and land confiscation, ethnic relations, and the need to confront long-standing Bamar chauvinism. On anniversaries related to the Rohingya genocide, we organized actions in Muslim neighborhoods that connected solidarity with the Rohingya to broader global struggles, including solidarity movements for Palestine.

People carried banners into the streets expressing remorse for the role that members of the ethnic majority had played, directly or indirectly, in the persecution of the Rohingya. Looking back now, it is clear that while many people sincerely expressed regret, others treated such gestures as tactical tools for anti-coup mobilization; deep down, many still held Bamar nationalist views.

In mid-April, the National Unity Government (NUG) was formed in exile, and several leaders from grassroots movements were incorporated into its structure. But many of their strategies and decisions were difficult for us to understand. While young people were still risking their lives by staging flash protests in the streets, the NUG began calling for “silent strikes,” asking people to stay home and shut down economic activity instead of protesting publicly.

At the same time, internet shutdowns continued, making communication increasingly difficult. In response, we launched the Molotov Newsletter project in April. Our editorial collective were all leftists and the paper was published weekly.

We printed and distributed physical copies in Yangon. The first issue, released in April, received an unexpectedly strong response: we distributed about 5000 printed copies there. Later that same month, the authorities declared it an illegal publication. Ironically, in the atmosphere of that time, this only made it more popular.

Since it was difficult to reach other regions physically, we uploaded the newspaper’s PDF online so people in different areas could download and distribute it themselves. Each issue received around 30,000 to 50,000 downloads on average.

Some of those who went to the jungles for training returned to the cities after only a month or two, and armed resistance began to appear in urban areas. Could you talk about that period?

Around May, some of those who had gone to the jungle for military training began to return to the major cities. They brought weapons with them and began carrying out urban guerrilla operations. Weapons started circulating in Yangon, and from then on, many young people joined flash mob protests during the day and took part in guerrilla actions at night.

In August, the military raided an apartment on 44th Street in Yangon that served as a base for a group of young activists. Shortly before the raid, those young activists had planted a bomb beneath an anti-junta banner; when police came to remove the banner, the device exploded. Later, we learned how the location had been exposed. A taxi driver who regularly worked with the group had been arrested by the military. He himself had actively supported anti-junta activities after the coup and was someone we trusted. Under brutal interrogation, he was forced to reveal the location of the safe house on 44th Street.

On the day of the raid, five people leaped from the rooftop in a desperate attempt to escape arrest. Two were killed instantly when they hit the ground, while three others were critically injured and taken to hospital. Inside the apartment, three more were captured alive. The survivors were later charged with the illegal manufacture and possession of explosives and sent to prison, where two of them died behind bars.

Only one person managed to escape that day. He hid for twelve hours beneath a small rooftop “shelter”, barely daring to move as soldiers searched the building below. Under cover of darkness, he finally slipped away and later crossed the border illegally into Mae Sot.

In the beginning of 2024, Ko Htet organized the funeral for the boy who fled 44th Street raid. The funeral turned into a protest. (Photo: El Kylo Mhu)

In the winter of 2023, he fell ill with what should have been a treatable disease, but without proper identification documents, he was unable to receive adequate medical care in Thailand. He eventually died in Mae Sot. I helped organize his funeral, and what began as a farewell soon turned into a protest.

After the 44th Street raid in Yangon, more young people, driven by outrage, joined assassination operations in the city. They named their group the “44th Street Urban Guerrilla Group,” and revenge became a major motivation behind their actions.

Personally, I always felt conflicted about these operations. I never actually aimed a gun at anyone. But because I worried about those comrades—most of them Gen Z kids—I often helped in other ways, keeping watch or driving them to and from operations. Step by step, I found myself involved anyway. For me, killing someone, or even seeing someone die in front of me, is extremely difficult to bear. It is a line I have never been able to cross emotionally.

During one of the operations, I saw a military affiliated woman shot. She collapsed right in front of me. For the next two years, she kept appearing in my nightmares.

One day in 2023, I received a call from a stranger’s profile on Facebook Messenger. When I answered, it turned out to be one of the comrades from 44th Street who had been arrested. He had briefly gained access to a phone while being taken to court and used the chance to call me. He told me that the woman we believed had been killed was actually alive and was now testifying against him in court. I don’t think he expected my reaction. Hearing that she had survived, I felt an enormous sense of relief.

During that first year after the coup, how would you describe the relationship between leftist movements and the broader anti-coup revolution?

In the first year after the coup, leftist organizing was highly structured. The revolution enabled our networks to expand rapidly. Many young people who had previously been apolitical or deliberately kept away from politics became radicalized, while those who already shared similar values were finally able to find one another.

Both the streets and the public sphere became spaces where different political forces competed for hegemony within the movement. At that time, one of the slogans raised by the General Strike Committee was “Uproot the Fascist Military,” and it quickly spread and became widely popular. Another slogan people embraced was, “We Have Nothing to Lose but Our Chains,” from the Communist Manifesto. I even printed these slogans on T-shirts, and they were warmly received by protesters.

Leftist language began to enter the revolutionary space in a visible way. More and more people used the vocabulary of leftist struggle and anti-fascism in street protests. Through Molotov Newsletter, we tried to provide historical context, explaining what fascism and anti-fascist movements actually meant, so that these slogans would not remain merely emotional expressions but become part of a deeper political consciousness.

Anti-fascist protest songs were also created from the leftist community to remind people that, historically, many forces that once claimed to fight fascism eventually became oppressive themselves. That was not a path we wanted to follow. For example, when Aung San Suu Kyi stood alongside the military at the International Court of Justice, defending Burma against accusations of genocide, many of us saw that moment as her becoming an accomplice of fascism.6

II. Leftist Movements

During your formative years, how were people able to access leftist or anarchist ideas in Burma?

Leftist forces in Burma have long existed under heavy repression. When I was a teenager, books about contemporary student movements were extremely difficult to find. There were only a handful of books covering Burma’s history after independence. By contrast, there were plenty of works about the monarchy and the British colonial period. In official education, anti-colonial nationalism dominated the historical narrative, while discussions of resistance movements and social struggles after independence were often erased altogether.

Most writings on post-independence resistance or alternative political thought were published abroad following different waves of exiles, and bringing such books back into the country was difficult and sometimes dangerous.

Before 2007, internet access was still very limited in Burma. To hear perspectives that differed from official propaganda, we relied largely on foreign radio broadcasts such as the BBC or Radio Free Asia. At the time, some propaganda and literary materials from the Burmese Communist Party circulated, along with a publication called Revolution (အရေးတော်ပုံ), which we could occasionally access online in fragments. We could also find some materials related to the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU). But it is important to remember that, in those days, listening to so-called “enemy radio stations” or reading banned publications could lead to serious punishment, including imprisonment.

The ABFSU has been the most important leftist student network in Burma. It was founded in 1936, when Burma was still under British colonial rule, and later played crucial roles both in the struggle for independence and in repeated anti-military movements.

After the military coup in 1962, student protests were brutally crushed, and the regime blew up the historic student union building at Rangoon University. Yet student resistance did not disappear. New waves of student protests erupted in 1974, 1975, and 1976. Then, during the nationwide pro-democracy uprising in 1988—the so-called 8888 Movement—the ABFSU flags returned to the streets and again became a symbol of resistance against military rule. Afterward, the military authorities frequently labeled the organization as a communist front or subversive force. When I was in university, I helped establish an ABFSU branch on my own campus.

At the same time, the military’s propaganda machine consistently portrayed the Burmese Communist Party as one of the main sources of national instability and division. Ironically, after General Ne Win seized power in 1962 and established a decades-long military dictatorship, the only legal political party allowed by the regime—the Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP)—claimed to follow socialism, promoting what it called the “Burmese Way to Socialism,” which in practice meant economic isolation, centralized control, and authoritarian rule.

Years of economic decline and social stagnation under this system led many people to associate poverty and repression directly with socialism. As a result, terms like “communism,” “socialism,” and even “leftist” became deeply stigmatized in public discourse. For many people, these words evoked fear or distrust. Because of this historical experience, mobilizing people around leftist ideas has always been extremely difficult in Burma.

When and how did you begin organizing actions in an anarchist way?

Around late 2013 and early 2014, we began forming anarchist reading groups and building networks for action. It was a very particular political moment. Formal military rule had ended in 2012, but Aung San Suu Kyi had not yet taken office—those years were widely described as a transition period. The military managed what it called a democratic transition; some political prisoners were released, and activities previously banned—such as public gatherings and publishing—became partially legal again. Civil society organizations began to emerge, and for a moment, it felt as if the country was moving toward normalcy.

At the same time, Aung San Suu Kyi traveled around the country promoting a strategy of nonviolence and electoral change. She encouraged people to transform Burma through voting, but she did not support protests on the ground. Meanwhile, we became involved in organizing protests around land confiscation affecting farmers, workers’ labor rights, and later the student movement against the Thein Sein government’s National Education Law.

An action carried out by Anonymous Burma in Yangon, 2014.

In 2014, we created a group called Anonymous Burma and began carrying out actions under that name. Even in that period, organizing open street protests was still difficult and risky. So we wore masks, burned parliamentary posters in city centers, and set off fireworks to draw attention. Some people began calling us Burma’s version of “antifa,” and individuals with similar political views contacted us wanting to join.

Zin Lynn, once a legendary leftist activist, now a political prisoner, was also part of our group Anonymous Burma. He had been a leading figure within ABFSU and was also a musician who wrote many revolutionary songs, including the anthem of ABFSU. He introduced generations of young protesters to classic revolutionary songs—writing Burmese lyrics for Bella Ciao, Do You Hear the People Sing, and The Internationale, so they could be sung in the streets, not just remembered from afar. After the violent crackdowns of March 2021, he went to the jungle for military training, later returned to Yangon to participate in urban guerrilla actions, and was arrested in September that year.

He remains in prison today. You can see many leftist activists in exile paying tribute to him in their publications and during live performances.

It was also during this period in Yangon that we began working with Food Not Bombs Burma. Kyaw Kyaw, the lead singer of the punk band Rebel Riot, had started organizing Food Not Bombs activities in Yangon in the early 2010s, and many of their political songs deeply influenced us. From then on, Food Not Bombs, Anonymous Burma, and ABFSU often worked together in protests and political/social organizing.

In 2015, Burma held its first election of the transition era, and many ordinary people felt hopeful about the country’s future. But our resistance activities continued. That year, we organized what became known as the “Long March,” calling on students to march from Mandalay to Yangon in protest against the newly introduced National Education Law, which centralizes control over universities and increases state—and indirectly military—control over education. Thousands walked 600 km starting from Mandalay, and the government brutally cracked down in Letpadan, a city north of Yangon.

With elections approaching, supporters of Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD were hostile toward our movement. They believed our protests would harm the election and disrupt the democratic transition. In their view, we were causing trouble at a critical political moment.

It seems that, faced with the common enemy of military rule, the relationship between the Burma leftists and Aung San Suu Kyi was often ambiguous—sometimes cooperative, sometimes competitive.

In fact, I have never voted for the National League for Democracy. In 2015, I did not vote. I also did not vote in the 2020 election. At the time, parts of the left started a “No Vote” movement. The only time I ever voted in Burma was during the 2008 constitutional referendum, and I voted against the constitution.

In reality, before Aung San Suu Kyi came to power, much of Burma’s left had supported her. Since the 1990 election, ABFSU had strongly backed the NLD. When I was a teenager, I also took part in youth campaigns demanding her release from house arrest.

However, after her release in 2010, we soon realized that we could not agree with many of her policies and political agendas. For instance, while we demanded the complete abolition of the 2008 Constitution, she chose to accept its framework and participate in elections within it. Meanwhile, many large-scale mining projects continued under her administration, including the highly controversial Letpadaung copper mine, where we participated in protests against environmental damage and forced land seizures. Many of these projects had originally been signed during military rule with foreign companies, including Chinese firms. Instead of stopping them, her government responded harshly to local resistance.

The same was true for projects such as the Chinese-backed Myitsone Dam in Kachin State, where protests were also suppressed. Her administration promoted economic development and foreign investment, but the result was often land confiscation and the displacement of local communities.

The final break came with the Rohingya genocide in 2017. When she traveled to the International Court of Justice, some of us still hoped she might expose the military’s crimes. Instead, she publicly defended the military. Soon afterward, NLD supporters put up posters across the country showing Aung San Suu Kyi standing side by side with military leaders, with the slogan: “We stand with Aung San Suu Kyi.”

For many of us on the left, that was the moment of definitive rupture.

III. The Waning of the Revolution

On October 7, 2023, mainstream “revolutionary circles,” including figures connected to the NUG and many representatives of the Bamar majority, openly expressed pro-Israel positions. Toward the end of 2025, when ABFSU issued a statement condemning what it described as US imperialism following the American intervention in Venezuela and the arrest of Maduro, it triggered intense backlash in Burma, with many people accusing ABFSU of being communist. In your view, when did the left begin to lose its mobilizing power?

In the first year after the coup, leftists and anarchists finally found a battlefield where we could play a real role. At that time, we still had strong mobilizing power and were able to bring many left-wing issues into public discussion. Even into 2022, many activities continued, though increasingly underground. But as the initial revolutionary energy began to fade, leftist movements themselves also started to weaken.

By 2023 and 2024, the Spring Revolution had entered a period of decline. The military kept advancing and consolidating control, while forces on the revolutionary side became increasingly fragmented and disorganized. Some revolutionary leaders openly made homophobic remarks, and reports of systematic sexual and gender-based violence emerged in certain so-called “liberated areas.” Yet under the banner of revolution, such issues were often deliberately downplayed or concealed, because many feared that internal criticism would weaken resistance against the junta.

Many comrades I once struggled alongside are now armed. Five years have passed. They are no longer the same people. The gun has become their form of power.

Those youth joined armed resistance out of anger and hatred toward military rule. But as the war dragged on, problems within the National Unity Government itself became more visible, and many fighters began to feel disillusioned. They had taken up arms to resist oppression, only to find that structures of power and hierarchy also existed within the revolutionary camp, the NUG leadership did not seem fundamentally different from the junta they opposed.

As a result, more and more fighters chose to leave the jungles. Because of documentation and mobility restrictions, many could not travel far, and a significant number eventually ended up in border towns like Mae Sot.

During the early phase of the revolution, in Molotov Newsletter, we repeatedly stressed that armed resistance must be guided by political values, or else the struggle could degenerate into fragmented warlordism. But in reality, most People’s Defense Force units today are not politically oriented; their only unifying political position is opposition to the military junta. Similarly, any ethnic armed group that fights the military is automatically seen as a legitimate political force, often without further scrutiny.

Yet many of these armed groups remain organized primarily along ethnic lines, and their political communities are built around ethnic identity. This risks reproducing new forms of ethno-nationalism rather than overcoming them. Even groups widely regarded today as among the most progressive, such as the BPLA (Bamar People’s Liberation Army), still operate within this framework to some extent. The difference is that they are more familiar with progressive discourses, and they attempt to regulate their conduct through such values, which is why they are still seen as one of the few armed groups that seriously engage with political questions.

Now it is the fifth year after the coup, the military has begun organizing what many observers call a sham election. How do you understand this moment?

Many people who left their jobs as part of the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) have eventually been forced to return to the very systems they once resisted, simply in order to survive. Others have sought asylum in third countries [after to Thailand]. The boycott movements that began in 2021 have become increasingly difficult to sustain. The military understands this reality very well, and it is precisely under these conditions that it has moved forward with what many see as another staged election.

Some political forces that stood on the margins of the NLD camp during the early days of the uprising, such as the People’s Party, are now participating in this widely criticized electoral process. At the same time, candidates in the election increasingly speak of “ceasefire” and “peace”—language that would have been almost unimaginable just a few years ago, when revolutionary momentum was still there.

I think that one important reason we have reached this point is that the National Unity Government (NUG) imposed its leadership on what initially was a spontaneous uprising led by young people, especially Gen Z protesters. Soon after the protests began, the NUG emerged, and most of its ministers came from the generation shaped by the 1988 uprising and the 1996 student movement. At the same time, some movement leaders who had strong influence among young people were incorporated into the structure, often as tokens, so that the leadership would not appear completely disconnected from the younger generation.

For example, the NUG emphasizes what it calls representative politics—ensuring that women make up around half of leadership positions, or that different ethnic groups are included. But this does not necessarily mean that those women representatives oppose patriarchy, nor that ethnic representatives genuinely fight for the collective right of their communities. Often, such representation serves more as a display of diversity.

People still hate the military junta, but they are also tired of the Spring Revolution itself. Many who once devoted themselves fully to resistance are slowly returning to ordinary life, worn down by reality. I feel this personally. In the first year after the coup, I could devote myself entirely to the revolution. Now, like many others, I also struggle to survive.

From my perspective, the “Spring Revolution” has already failed. This is very difficult to say openly, and after so much sacrifice, many people cannot accept it. But I do not think we can continue living under the illusion that victory is just around the corner. If one day we want to win again, the only path forward may be to return to political education, to organizing young people, and to reclaiming the terrain of ideology and values.

At the same time, I must add that my experience and my assessment of the revolution do not represent all leftist resistance fighters in Burma. The comrades who went into the jungles for military training and continue to fight in ethnic armed territories or in regions like Sagaing in central Burma experience the revolution very differently.

More recently, in November 2025, the Spring Revolution Alliance formed. Many armed groups joined this alliance and moved away from the leadership of the National Unity Government. They pledged to guide themselves through shared progressive principles. For many people, this alliance still represents a remaining hope for unity within the resistance.

IV. Exile

On one hand, it feels as though revolutionary momentum is fading. On the other, here in Thailand, it seems that within the Burmese exile community, the “revolution” has become an NGO-driven industry. How do you see this?

In fact, this trend did not begin after the Spring Revolution. Its roots go back to the earlier period of democratic transition.

After Aung San Suu Kyi came to power in 2015, Burma did experience a period of relative opening. For many people, it was the first time they felt Burma was reconnecting with the wider world. It was also during those years that a large number of Western NGOs entered Burma, bringing substantial funding into civil society.

Many former grassroots activists began establishing their own NGOs and became part of this new institutional ecosystem. Agendas were often shaped by donors, and activists increasingly worked according to funding priorities. Activism gradually became a profession.

Between 2015 and 2020, you could clearly see that many projects and programs within civil society were shaped by externally driven agendas, sometimes poorly aligned with the actual needs of communities on the ground. During this process, it was painful to watch how some activists who had once been full of energy and conviction were gradually absorbed—and sometimes corrupted—by the NGO system.

Now, five years after the coup, we see the emergence of yet another generation of so-called NGO activists. Some use the revolution and people’s suffering to build personal careers—obtaining scholarships abroad, entering international NGO networks, and becoming spokespersons for Burma’s democratic struggle. Yet in reality, many of them are increasingly distant from what is happening on the ground.

For my part, I have always followed a different logic. I maintain my own small business so that I can sustain myself independently while participating in social movements. Whether during the transition period or now, my comrades and I have continued to organize according to anarchist principles, relying on crowdfunding and mutual aid rather than writing budgets, applying for grants, or submitting project reports to keep our work going.

Could you describe how you are involved in social organizing now, in exile?

At this stage, most of what I do focuses on organizing within the exile community. I arrived in Mae Sot at the end of 2021. From then on, I stopped my work with the General Strike Committee and shifted toward local community organizing.

Mae Sot hosts a large transient population. Many are young people; many others are families who fled with their children. Quite a number of them once participated in the Civil Disobedience Movement and, after leaving their jobs, were blacklisted by the military authorities. Unable to leave Burma legally, they ended up stuck in this border town in a kind of temporary existence. Mae Sot is also a place of rest and supply for many PDF fighters. Some are still active in jungle-based resistance and only come here occasionally to rest. Others have left the battlefield because of injuries or disillusionment and are trying to survive here for now.

Some of these people may eventually resettle in third countries, but I believe many will one day return to Burma. For now, almost everyone here lives in a state of suspension—without stable work and without a real home. Yet many revolutionaries do not see these displaced people as part of the revolution anymore. Gradually, I realized that this is exactly where we need to work: organizing those who are stranded in these border spaces.

So I started what we call the “Mae Sot Home,” using it as a platform to organize everyday activities—football matches, film screenings, reading groups—to bring together people from very different backgrounds: migrant workers, exiled resistance fighters, Bamar, Karen, and members of Muslim communities. Through these gatherings, we talk about anti-fascism, gender issues, and ethnic relations.

An iftar during Ramandan in Maesot, 2024. Food Not Bombs Mae Sot providing food to the Muslim community.

At the same time, together with other comrades, we established Food Not Bombs Mae Sot. We cook meals for displaced Burmese refugees, but not in a charitable, top-down way. Instead, we want to convey ideas of mutual aid and solidarity. Some people involved in armed resistance mock or even attack us, saying that now is the time for weapons, and that Food Not Bombs sounds like anti-war activism. But in reality, we were already organizing Food Not Bombs activities in Yangon in the early 2010s, long before the coup. We are fighting the military today so that one day we can live peacefully again—not so that society remains permanently militarized.

Within the work of Mae Sot Home, football has become one of our most important organizing tools, partly for safety reasons. Many people here lack legal status, and public gatherings often exist in a gray zone. We once tried to organize a concert and were reported to the authorities, which forced us to change venues at the last minute. Football matches, however, are easier to hold, since the sport is widely accepted and popular locally. More importantly, football has almost no barriers to entry, and Burmese migrant workers in Mae Sot already have a strong football culture. It becomes an easy way to bring together young exiles and migrant workers. We also organize women’s teams and youth matches, and during these events, we discuss issues such as domestic violence, gender equality, and anti-fascism.

Some people who had migrated here before the coup originally felt distant from the revolutionary movement; but through playing football together, they gradually began to engage in conversations and understand the struggles others are facing. At the same time, some young people who arrived after the coup, especially those from big cities, sometimes become absorbed in their identity as “revolutionary exiles” and look down on those who came earlier—often migrant workers or Muslim cross-border traders—seeing them as not progressive enough. But in reality, racism and Bamar chauvinism also exist within the revolutionary movement itself. Rather than constantly drawing lines between friends and enemies, I think it is more important to leave room for people to change.

Burma’s education system has produced generations shaped by nationalist prejudice. Now, through the ruptures caused by the coup, revolution, and exile, we may finally have a chance to win some of them back.

Further Reading

- Unhappy Is the Land that Needs Heroes

- “We are the Palestinians of Burma“—Interview with the Progressive Muslim Youth Association

-

Many Burmese anarchists use the English term “Burma” instead of “Myanmar” because of the latter’s association with the ruling military regime since its official adoption in 1989. Other Burmese leftists prefer “Myanmar” despite this association, because “Burma” (also preferred by the liberal National League for Democracy) is linked more closely to the Bamar majority, as well as to British colonialism. The terms are identical in Burmese; the different English spellings represent the literary and colloquial pronunciations. Both terms derive from the Bamar term for their own ethnic group. ↩

-

Launched after the February 2021 coup, the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) of Burma is a nonviolent resistance movement, in which civil servants and workers went on strike and refused to cooperate with the junta, becoming a central force in the Spring Revolution despite severe repression. ↩

-

The 2008 Constitution, drafted under military rule and approved in a controversial referendum shortly after Cyclone Nargis, is widely seen by opposition forces as a tool to preserve military control. It reserves 25 percent of parliamentary seats for the military, effectively granting it veto power over constitutional amendments. ↩

-

The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) is a United Nations-endorsed international norm adopted in 2005, designed to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. It posits that sovereignty implies responsibility, and if a state fails to protect its population, the international community must intervene via diplomatic or, as a last resort, military means. ↩

-

The practice of banging pots and pans from balconies at dusk comes from a traditional Burmese folk belief that making loud noises at twilight drives away evil spirits. ↩

-

In December 2019, then State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi appeared before the International Court of Justice in The Hague to defend Burma against charges that the military had committed genocide against Rohingya Muslims. ↩