In 1970, the United American Indians of New England declared Thanksgiving Day a National Day of Mourning. In addition to decrying centuries of manipulation and violence against them by settlers and their descendants, they were responding to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts rescinding an invitation to Wamsutta Frank James, a member of the Aquinnah Wampanoag, to speak at the 350th anniversary of the landing at Plymouth Rock. The organizers had canceled the invitation after learning that James did not intend to perpetuate the white fantasy of peaceable Native-Colonists relations, but to tell the damning story of how the colonists had treated the region’s original inhabitants. That same year, the American Indian Movement disrupted a Thanksgiving reenactment at Plimouth Plantation, stormed a replica of the Mayflower, and painted Plymouth Rock red.

In recognition of the Day of Mourning, and in hopes of offering important context to colonial mythology about early Thanksgivings, we present the story of Metacomet’s War, one of the most ambitious early efforts to resist the colonial conquest of what came to be called North America.

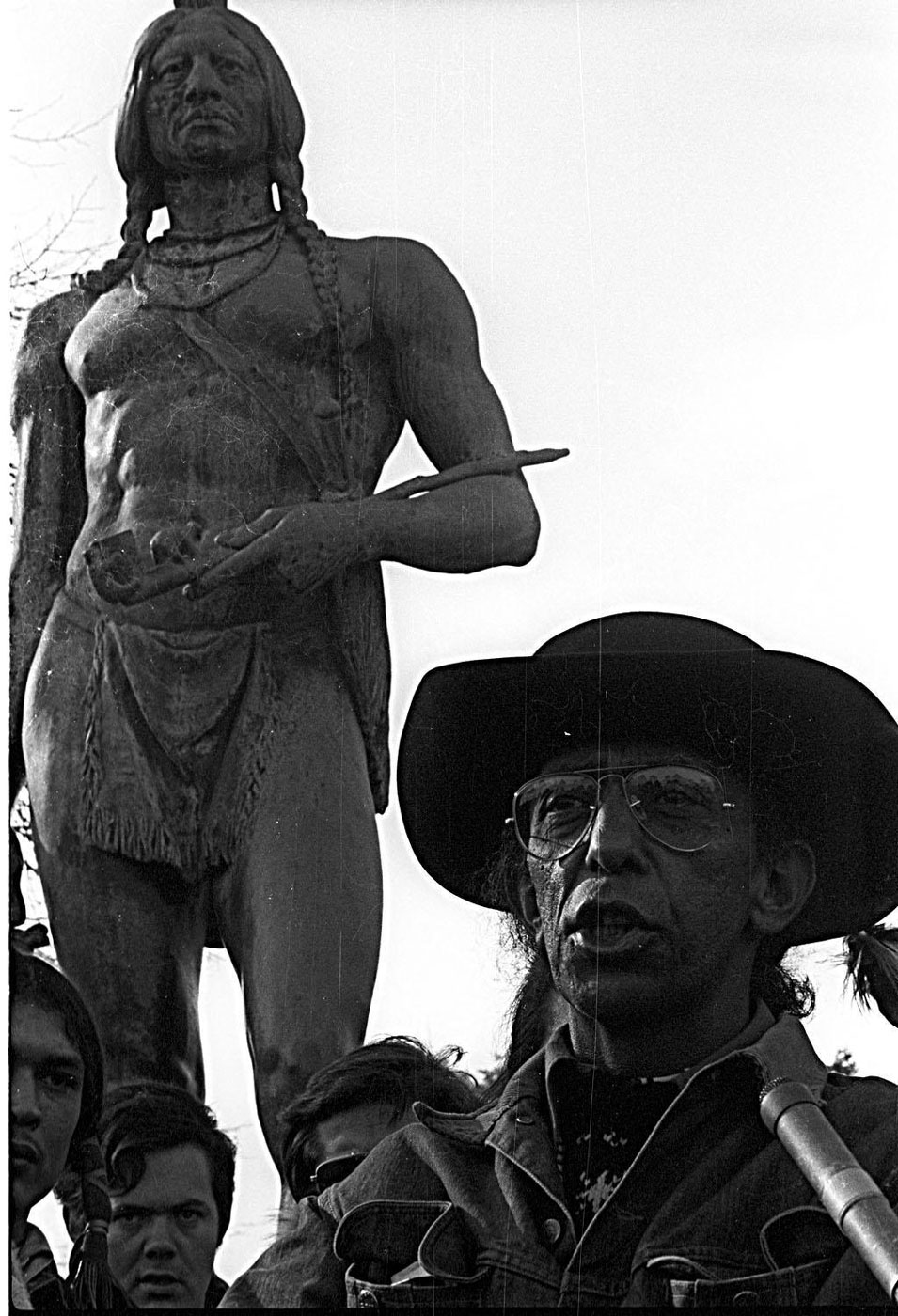

A Native American demonstration at Plymouth Rock. The banner reads “In the spirit of Metacom,” another spelling of Metacomet. Photo: United American Indians of New England.

America, as we know it, was never inevitable. The story of Metacomet’s War highlights this. While this struggle saw the end of large-scale Native sovereignty in colonial Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, it could just as easily have concluded with the end of British colonization in the region. Rather than conceiving of history as the inexorable unfolding of a Eurocentric notion of progress, we understand it as an endless interplay of contingencies and possibilities, a story that is never really concluded.

In place of the disaster of the present day, in which borders are impassable, wealth and power have accumulated in the hands of a privileged class, and the same structures that nourish us are destroying the biosphere that we all depend on for life, we can imagine a world comprised of a wide range of different societies living together in relative equilibrium, in a sustainable relationship with the land and its other inhabitants. “Two distinctly different cultures met,” as Wamsutta Frank James described the encounter at Plymouth Rock. “One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it.” All human beings and living things have suffered as a result of the victory of the colonists against Metacomet and his companions. But the story is not over yet.

For want of sources about more of the ordinary participants in these events, we have been forced to concentrate on well-known figures like Metacomet and Weetamoo, but we should not settle for a way of seeing the past that reduces entire communities to their supposed leadership. Likewise, when we attempt to reconstruct this history, it’s important to remember that nearly all of the information we have access to about them reaches us through the channels of settler society. Even the best-intentioned accounts still draw heavily from colonial narratives. We simply don’t know the other side of the story. Returning once again to the origin of our present society, we can at least catch a glimpse of what we’ve lost.

This is an excerpt from a larger, multi-volume work about John Adams and colonial New England. For resources on Indigenous anarchism, you could begin with “Locating An Indigenous Anarchism,” by Aragorn!, or the Indigenous Anarchist Federation. You can find a reading list cataloguing some of the intersections between Indigenous and anarchist thinking and action here.

Metacomet’s War, 1675-1676

“I am determined not to live till I have no country.”

-Metacomet

The Wôpanâak (Wampanoag Confederacy) were among the only Native Americans to greet colonists at Plymouth in 1620. The Massachusett to the north and the Nauset to south both eyed the newcomers suspiciously, if not with outright hostility. Two decades of European diseases had reduced their numbers by 60-90%, in some cases destroying entire towns, including those belonging to the Patuxet.1 For fifteen years, British explorers and fishermen had been kidnapping Native people throughout the Northeast and taking them back home as slaves, sources of intelligence on the region, and guides for future expeditions, in order to entice potential colonial investors. The Nauset of southern Cape Code Bay, who had suffered greatly from the loss of seven stolen members in 1614, often reminded Plymouth of the transgression.

But Massasoit Ousamequin, the paramount sachem of the Wôpanâak, broke ranks and sent Tisquantum (Squanto) to help the settlers before their second winter. That fall, Ousamequin “came with 90 Wampanog men and brought five deer, fish, all the food and Wampanog cooks,” to celebrate Nikkomosachmiawene (Grand Sachem’s Council Feast). This celebration, now whitewashed and sanctified as one of the First Thanksgivings, was likely marked “by traditional [Wôpanâak] food and games, telling of stories and legends, sacred ceremonies and councils on the affairs of the nation.”

A year later, Ousamequin signed a treaty with Plymouth in hopes of preserving the Wôpanâak’s homes against the British and the more powerful Narragansett to the west. Ousamequin kept much of his confederacy out of the Pequot War in the 1630s, giving a much-needed advantage to the colonists.

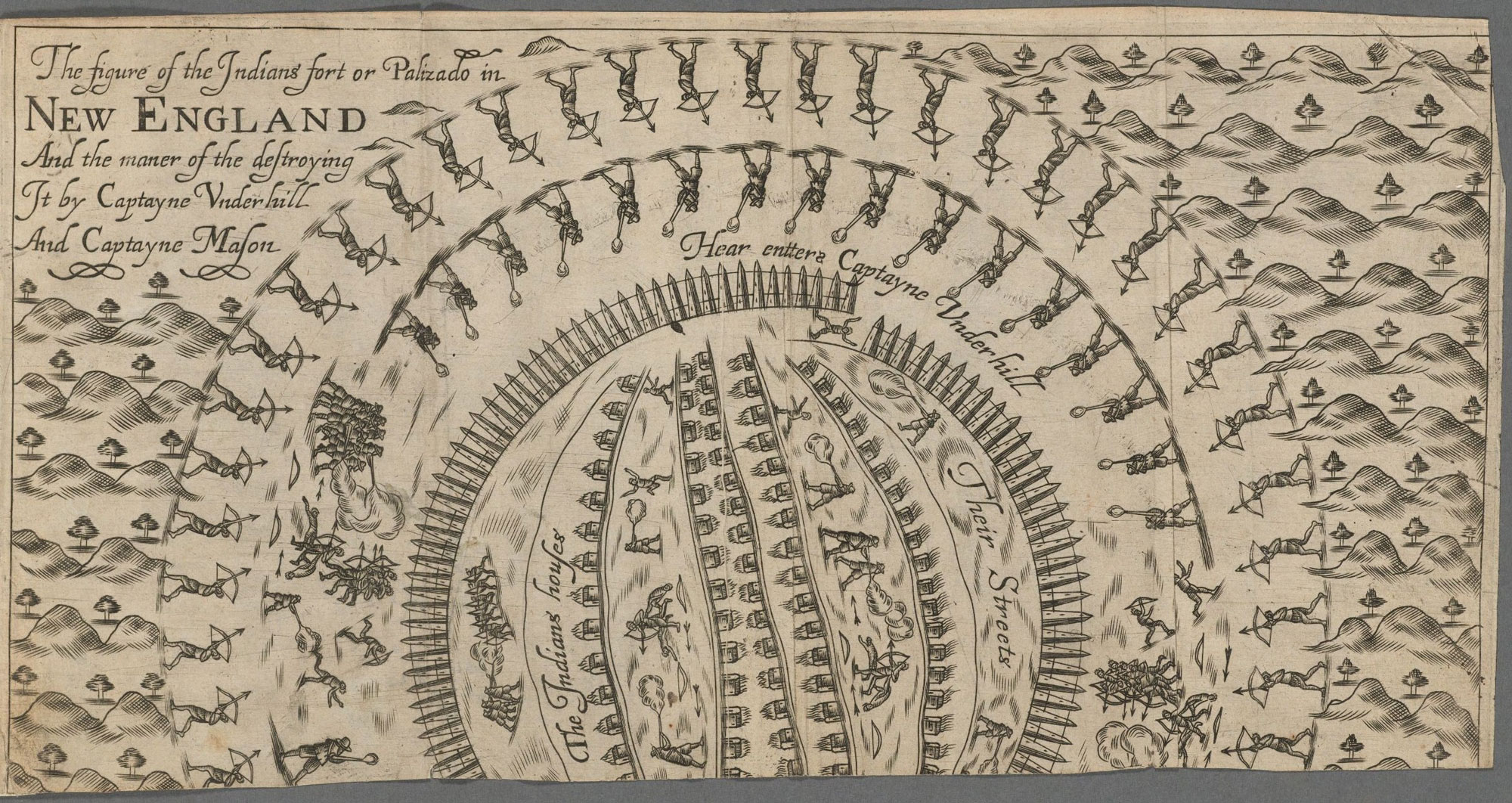

The conflict was over the Connecticut River Valley, a lush region coveted by Dutch, British, and Native fur traders and farmers. The British won the war after storming the Pequot village of Siccanemos along the Mystic River in Connecticut. They lit the fortified settlement ablaze, slaughtering or burning to death all but fourteen of the 600-700 Pequot trapped inside. Of the fourteen villagers who escaped this fiery death, seven managed to flee into the woods. Colonists captured and enslaved the others.

A colonial depiction of the British assault on the village of Siccanemos.

“Why should you be so furious (as some have said),” asked Captain John Underhill, leader of the attack, in his recollections of the massacre. “Should not Christians have more mercy and compassion?” To Underhill the answer was simple: read the Old Testament. The Pequot had sinned “against God and man” and “sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents.”

Another leader of the assault, Puritan Captain John Mason, agreed, later recalling that

“God was above them, who laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to scorn making [the Pequot fort] as a fiery Oven… Thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen, filling the Place with dead Bodies.”

When the victorious colonists returned home to Massachusetts Bay, they were greeted by a colony-wide day of feasting2 and “of thanksgiving kept in all churches for the victory obtained against the Pequots, and for other mercies.” The act of giving thanks to God was common in 1600s New England. From Catholicism to the Reformed Christianity of the Puritans and Separatists, thanksgiving was built into the day-to-day lives of the most pious.

At the Last Supper, according to Christian folklore, Jesus “took the bread, and giving thanks, broke it,” then “took the chalice, and once more giving thanks, he gave it to his disciples.” These acts are the inspiration for the Eucharist, in which the Last Supper is reenacted and bread and wine communally shared. The Eucharist, from ecclesiastical Greek eukharistia, “thanksgiving,” is the backbone of most Christian worship. It is telling what things warranted fasting and official proclamations of thanksgiving in colonial New England: good harvests, the safe arrival of ships across the Atlantic, new settlements, and military victories over heathen insurgents.

After the Pequot War, colonists hunted down and enslaved the three hundred surviving Pequot. Women and children under the age of twelve were divided among the Mohegans and British in Connecticut and Massachusetts, while the men were sold into slavery in Bermuda. The British made it illegal for them to use their own name or live in their own villages, declaring the Pequot extinct.

When Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop received a group of Pequot slaves after the war, Roger Williams,3 the founder of Rhode Island, wrote to him. Saying, “It having pleased the Most High to put into your hands another miserable drone of Adam’s degenerate seed,” Williams asked if he might have one of the child captives for himself: “I have fixed mine eye on this little one with red about his neck.”

The ship that took the Pequot away from their homeland, the Desire, exchanged them in Bermuda for Africans, returning with Massachusetts’ first proper shipment of African slaves. This inaugurated 140 years of African bondage in the Bay State. The practice of exporting captured Native Americans in exchange for African slaves was to become a New England tradition.

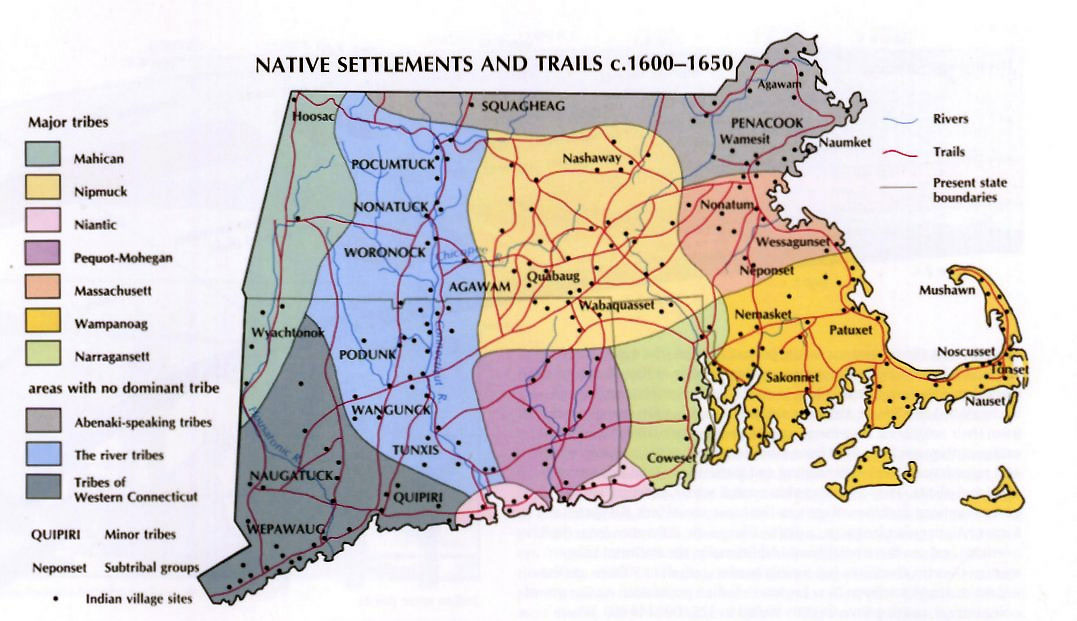

By the mid-1600s, roughly 10,000 Native Americans remained free in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. A thousand Wôpanâak lived between Plymouth Colony and their capital town, Montaup (Mt. Hope), in eastern Rhode Island; 2400 Massachusett and Pennacock (Pawtucket/ Merrimack) between the Massachusetts Bay Colony and western Maine; 2400 Nipmucs in central and western Massachusetts; and 4000 Narragansett in Rhode Island and Connecticut. Smaller lesser-known autonomous villages existed as well, with no unifying figure or government holding sway over all 10,000.

While they fared better than the Pequot and other peoples in the region, by the time Massasoit Ousamequin died in the early 1660s, Wôpanâak life was deteriorating. Ousamequin’s son, Wamsutta (Alexander), ruled for a year, during which he began to sever ties with the Massachusetts colonists and started selling Wôpanâak land to other Europeans. Accusing him of conspiring against Plymouth, colonists marched Wamsutta at musketpoint to their court and imprisoned him for three days. When Wamsutta died shortly after his release, his brother, Metacomet (known to the British as King Philip), assumed leadership of the confederacy.

Like Wamsutta, Metacomet understood that if things continued as they were, it could only mean further subjugation for the Wôpanâak. Left unchecked, the British could completely destroy their land, their culture, their freedom, and their lives as they had done to the Pequot. For Metacomet, who always maintained that Wamsutta had been tortured and poisoned by Plymouth, his brother’s death was proof enough. Though their father had aligned himself with the British in hopes of obtaining security, the Wôpanâak were learning that this military alliance did not protect their homeland or culture. Throughout the late 1660s and early 1670s, Plymouth repeatedly pressured the Wôpanâak to turn over more and more land, which Metacomet refused.

In addition, Wôpanâak culture was explicitly under attack by ministers like the Puritan John Eliot, who was christening Native Americans of the Northeast as “Praying Indians” and consolidating them into a dozen or more “Praying Towns.” Eliot’s converts were expected to assimilate into European customs, technologies, and lifestyles; the Praying Towns functioned as buffer zones between the more established European settlements on the coast and anti-assimilationist Native towns west of them. In 1663, Eliot translated and printed the Bible into Massachusett (Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God), publishing the first copies of the Christian bible in America.

John Eliot’s Bible.

Eliot especially tried to convert Native leaders, including Metacomet. But seeing Eliot as another settler out to manipulate, control, and destroy his people, Metacomet refused his advances. In one final dramatic encounter, “after the Indian mode of joining signs with words,” Metacomet ripped a button from Eliot’s coat and declared that “he cared for his gospel just as much as he cared for that button.”

Yet Metacomet was up against impossible odds—and the colonies were expanding by other means. By the 1670s, fifty years after the founding of Plymouth, the coastal centers of New England had taken root: Providence and Newport, Rhode Island; New Haven and Hartford, Connecticut; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Plymouth, Salem, Boston, Ipswich, and Springfield, Massachusetts; and Kennebunk and Portland, Maine. 80,000 colonists were spread throughout the region in roughly 110 towns, over half of which were in Massachusetts and parts of Maine (then a part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony). Though it’s hard to obtain numbers, these settlements likely included dozens of Native slaves, if not hundreds, as well as some slaves kidnapped from Africa.

In 1673, after the General Court of Massachusetts awarded Wôpanâak land near Montaup to a settler against the wishes of the Wôpanâak, Metacomet began meeting with Native leaders to discuss a self-defense league. Some sources suggest that Metacomet had been doing this since his brother’s death a decade earlier. In 1674, one of Metacomet’s advisers, a Praying Indian named John Sassamon (Wussausmon), informed Plymouth Governor Josiah Winslow of Metacomet’s intent. Metacomet was put on trial for conspiring against the colony, but nothing could be definitively proven.

An image of Metacomet from 1827. All the depictions of Metacomet we have access to are speculative, and most are stereotyped views from a colonial perspective.

An image of Metacomet from 1858. The wide range of different portrayals of this Indigenous leader show how little credibility colonial depictions of the Wôpanâak deserve.

When Sassamon’s body was found frozen beneath Assawompset Pond the following January, the colonists arrested three Wôpanâak men—Wampapaquan, Mattashunnamo, and his son Tobis. They were condemned by a white and Native jury and hanged in Plymouth in early June. During the executions, Wampapaquan’s noose broke; he was reprieved for a month, then killed by firing squad.

As a close friend of the accused, Metacomet took the executions personally, as many other Wôpanâak likely did. Fearing the worst, a settler friend of Metacomet’s, John Borden, went to Montaup to see if war might be prevented. Metacomet told him,

“The English who came first to this country were but a handful of people, forlorn, poor and distressed. My father was then sachem. He relieved their distresses in the most kind and hospitable manner. He gave them land to plant and build upon. He did all in his power to serve them. Others of their own countrymen came and joined them. Their numbers rapidly increased. My father’s counselors became uneasy and alarmed, lest, as they were possessed of firearms, which was not the case with the Indians, they should finally undertake to give law to the Indians, and take from them their country. They therefore advised to destroy them before they should become too strong, and it should be too late.

“My father was also the father of the English.4 He represented to his counselors and warriors that the English knew many sciences which the Indians did not; that they improved and cultivated the earth, and raised cattle and fruits, and that there was sufficient room in the country for both the English and the Indians. His advice prevailed. It was concluded to give victuals to the English. They flourished and increased. Experience taught that the advice of my father’s counselors was right.

“By various means the English got possessed of a great part of his territory, but he still remained their friend till he died. My elder brother became sachem. They pretended to suspect him of evil designs against them. He was seized and confined, and thereby thrown into sickness and died. Soon after I became sachem they disarmed all my people. They tried my people by their own laws, and assessed damages against them which they could not pay. Their land was taken. At length a line of division was agreed upon between the English and my people, and I myself was to be responsible. Sometimes the cattle of the English would come into the cornfields of my people, for they did not make fences like the English. I must then be seized and confined till I sold another tract of my country for satisfaction of all damages and costs. Thus tract after tract is gone. But a small part of the dominion of my ancestors now remains. I am determined not to live till I have no country.”

And so the war began.

The siege of Brookfield, August 2 to 4, 1675, during which Nipmuc warriors attacked colonial soldiers who retreated inside a fortified settlement. Although this illustration and the image at the top of this article were produced long after the fact by settlers seeking to justify colonial violence, today we can see them as depicting an understandable response to Native genocide.

Towards the end of June, a Wôpanâak force attacked and destroyed the Plymouth settlement of Swansea. A few days later, a total lunar eclipse affirmed Metacomet’s plan and strengthened the Native coalition. But retribution was swift and severe; a week after the attack on Swansea, a colonial force raided and destroyed the abandoned capital of Montaup. A year of horrendous fighting followed throughout Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and beyond. It proved devastating for all parties involved.

Metacomet’s forces attacked more than half of New England’s 110 European settlements during the war. Seventeen towns were completely destroyed by Native raids; some of them were never rebuilt. Conservative estimates suggest that one out of every ten of the region’s 16,000 white men eligible for military service died during the war; others estimate that fully 3000 of New England’s colonists were killed, and countless others injured and traumatized. Alongside the efforts of the Wabanaki Confederacy in Maine and Acadia, this is likely the closest a Native force came to halting and removing well-established colonies in the American Northeast. Skirmishes and small raids between British colonists and Native Americans backed by French Jesuits in Maine and Acadia escalated during Metacomet’s War and continued as a separate conflict for three years afterward.

In the late summer of 1675, when Nipmuc, Podunk, and Wôpanâak forces had driven settlers out of the Connecticut River Valley, “New England’s Breadbasket,” the settlers raised an expedition to collect the much needed crops they had abandoned. Without them, colonists feared they wouldn’t survive the winter. On the afternoon of September 18, when the hundred militiamen and teamsters transporting the crops stopped to eat roadside grapes, 700 Pocumtuc and Nipmuc warriors ambushed and slaughtered all but ten of them. Shortly after, a Native attack on the nearby settlement of Deerfield, recently built on Pocumtuc land, completely destroyed the village.

As the war progressed, fear of being enslaved in the Caribbean became a determining factor for many Native Americans. Weetamoo, the sunksqua (female sachem) of the Pocasset and the widow of Metacomet’s brother Wamsutta, cited this concern in her decision to join forces with Metacomet. In fact, Weetamoo felt so strongly about resisting enslavement at the hands of the British that she divorced her current husband when he sided with the colonists. Throughout the war, insurgents pleaded with Praying Indians to not submit to the colonists, saying that the British intended “to destroy them all, or send them out of the country for bond slaves.”

As with the images of Metacomet, the only depictions of Weetamoo are speculative and stereotyped. A contemporary colonial witness—if a biased one—described her differently: “A severe and proud dame she was, bestowing every day in dressing herself neat as much time as any of the gentry of the land: powdering her hair, and painting her face, going with necklaces, with jewels in her ears, and bracelets upon her hands.” By all accounts, Weetamoo was a powerful and widely respected leader, in contrast to the strict patriarchy of Puritan society.

Even when groups who had never taken up arms against the British began to surrender to them, as they did throughout the summer and fall, they made sure to specify that they surrendered on condition of not being enslaved and that they would not be sent out of the region. Colonists were quick to ignore such requests, labeling insurgents, Praying Indians, and non-combatants alike “complyers” with Metacomet.

In July, Plymouth officials sold 160 self-surrendered Native Americans into slavery. In August, Josiah Winslow and the Plymouth Council of War decided to sell another 112 captives; the resulting profits were essential to funding the war. In September, 57 more were “condemned unto perpetuall servitude”—and at the end of that month, 178 Native captives were sold to Captain Sprague and exported to Cadiz, Spain. This pattern of enslaving and exporting Native Americans regardless of their allegiances continued throughout the war.

In November, Plymouth Governor Josiah Winslow led a force of 1000-1500 Pequot5 and Muhhekunneuw (Mohican) soldiers and Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Plymouth militiamen against the Narragansett. Though the Narragansett had not yet joined the war, they had harbored and aided other Native combatants, elders, and children, and individual members had participated in raids. It’s possible that Winslow didn’t know the Narragansett weren’t directly involved in the war, or didn’t know the Native identity of towns he was attacking. Asked to hand over the Wôpanâak, Narragansett leader Canonchet declared, “Neither a Wôpanâak, nor the trimmings from a Wôpanâak’s nails, shall I deliver to the English!”

As the Narragansett withdrew west into Rhode Island, Winslow’s party pursued them through the bitter cold, destroying a number of their villages along the way. By December, the Narragansett had hidden themselves deep within the Great Swamp. Their fortified settlement, explains G. Timothy Cranston, “consisted of a natural ring of large trees with the spaces between filled in with wooden logs driven into the ground.” The only way in was across a large felled tree that lay above the swamp’s waters. In mid-December, Winslow’s men captured a Narragansett man and tortured him until he revealed the location of his people. At this point, unbeknownst to the colonists, some of their Muhhekunneuw allies met privately with the Narragansett and “promised to shoote high” over the Narragansetts’ heads.

When fighting started the morning of December 19, the Narragansett spent the first hour picking off militiamen as they tried to make their way across the bottleneck entrance. But once Winslow’s men breached the town, a massacre ensued. As the Narragansett defended themselves as best they could, militiamen and their Native allies mowed them down, setting fire to the Narragansett’s stores of winter corn and hundreds of their wigwams. Though some managed to escape into the frozen swamp, Winslow’s raid killed between 400-1,100 Narragansett, mostly non-combatants. The colonists and their allies took another 350 men “and above 300 women and children” prisoner. Victory, however, came at a heavy price. When the colonists finally retreated, one officer was so relieved that “with so many dead and wounded, [the Narragansett] did not pursue us, which the young men would have done, but the sachems would not consent.” Dozens of colonists died in the freezing cold on their way back to camp with over 200 wounded and dead all told.

Back in Plymouth, colonial officials auctioned the Narragansett to local households and shipped the others to the Caribbean, where they were likely exchanged for Africans. Neutral and ally Native Americans continued to suffer the wrath of colonial officials as well.

During the fall of 1675, between 500 and 1100 Praying Indians, who had been confined to their homes and denied access to their fields and muskets since the beginning of the war, were forcibly interned on Long Island, Deer Island in Boston Harbor, and elsewhere. Some Native historians believe that these numbers do not include forcibly interned non-Christian Native Americans, who may have numbered in the hundreds. The General Court of Massachusetts proclaimed “that none of the sayd indians shall presume to goe off the sayd islands voluntarily, uponn payne of death” and that colonists should “kill and destroy [Native fugitives] as they best may or can.”

The 95-year-old Tantamous (Jethro), a member of the Nipmuc who had not joined the rest of his family in becoming Praying Indians, protested their treatment; the Massachusetts Court had him whipped thirty times. Over the freezing winter of 1675-1676, hundreds starved and froze to death on Deer Island. Though the elderly Tantamous managed to escape the camp with eleven family members, by the time the camp at Deer Island was disbanded later that winter, all but 167 people had perished.

In 2010, the Natick Nipmuc and others gathered on Deer Island to remember the hundreds of Nipmucs and other native people who were forcible interned on Deer Island on October 30, 1675. Paul Hasgill, Chief of the Natick NIPMUC council, sprinkled tobacco in a ceremonial gesture.

In the course of this struggle, we can see at least one instance of colonial treason. Joshua Tift was the son of a white couple who had settled in Rhode Island near the Great Swamp around 1661. In the early 1670s, Joshua fell in love with and married Sarah Greene, the illegitimate daughter of a Wôpanâak woman and Major John Greene, a prominent Rhode Islander. It is said that from the day Joshua and Sarah met, they never attended another church service.

Tragically, Sarah died in 1671, shortly after the birth of their son Peter. Yet it appears that even after her death, Joshua remained loyal to the Wôpanâak and nearby Narragansett. When most colonists fled the area in 1675, Joshua stayed behind, eventually joining the Narragansett in the Great Swamp. Accounts conflict as to why he did and what happened next.

In one version of events, Canonchet, a Narragansett war leader, raided Joshua’s home in November 1675. After begging for his life, Joshua was enslaved to Canonchet. Taken to the Great Swamp, Joshua was forced to serve the sachem and fight alongside him. At least, this is what he said when the United Colonies accused him of High Treason.6

Another version of events suggests that Joshua went willingly into the Great Swamp, bringing the scalp of a British miller with him to prove his loyalty in defending the Narragansett. During Winslow’s raid on the swamp, Joshua was seen to wound or kill five or six colonists, including Captain Nathaniel Seeley of Connecticut. A kidnapped colonist enslaved in the swamp later testified that when a Narragansett leader fell and warriors began to run in panic, Joshua rallied them to cover the retreat of children and elders.7

Wounded while conducting a raid near Providence, Rhode Island a month later and taken prisoner, Joshua was recognized from Winslow’s attack and charged with treason by Providence militia captain Roger Williams. Captain Richard Smith and Plymouth Governor Josiah Winslow personally escorted Joshua from Providence to Smith’s Garrison in present day North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Within two days, Joshua was found guilty, hanged, and quartered—the only white man in the official history of Rhode Island to suffer such a fate. While we’ll likely never know whether Joshua joined the Narragansett under duress and to whom he was truly loyal, the fact that he had married a Native woman and hadn’t attended church in years was likely enough to seal his fate.

The Rhode Island law for High Treason may give us a sense of Joshua’s final, horrific moments:

“For High Treason (if a man)8 he being accused by two lawfull witnesses or accusers, shall be drawn upon a Hurdell unto the place of Execution, and there shall be hanged by the neck, cutt down alive, his entrails and privie members cutt from him and burned in his view; then shall his head be cutt off and his body quartered; his lands and goods all forfeited.”9

Like countless rebels before and after him, Joshua’s body became a physical and psychological testament: Indians can become Christian subjects (though disposable and viewed with skepticism, like the interned Praying Indians), but colonists may not turn Native! What’s the use of borders if we don’t fear crossing them?

A settler depiction of one of the defeats the colonial soldiers suffered.

With Montaup destroyed, Metacomet wintered in Schaghticoke, a refugee village of mixed tribes in eastern New York. Metacomet retreated there to enlist the help of the Muhhekunneuw (Mohican), Kanienkehaka (Mohawk), and others. Though the Muhhekunneuw initially swelled Metacomet’s Schaghticoke camp to 2,100 fighters, the Kanienkehaka responded to their long time adversary’s request for help by killing hundreds of Metacomet’s men and driving the rest of the Wôpanâak from the region.

While Wôpanâak, Narragansett, and other Native fighters attacked dozens of European settlements that spring, torching Lancaster, Medfield, Groton, Marlborough, Sudbury, and Providence and bringing the trade of New England ports to a halt, their time was running out. Some historians have speculated that they were defeated on account of the lack of Kanienkehaka aid. We can imagine that had the Kanienkehaka joined Metacomet’s coalition, or even the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) in general, they might very well have driven the British out of New England. This could have freed the region from European occupation for generations.

That winter, Massachusetts officials allowed two Praying Indians, James Quannapaquait and Job Kattenanit, to leave their confinement on Deer Island in exchange for meeting with insurgent leaders. While some older fighters were willing to begin peace talks, the younger generations objected, telling Quannapaquait and Kattenanit,

“We wil have no peace. Wee are all or most of us alive yet & the English have kild very few of us last summer. Why shall wee have peace to bee made slaves, & either be kild or sent away to sea to Barbadoes &c. Let us live as long as wee can & die like men, & not live to bee enslaved.”

But with lack of additional support, morale broke. By late spring, Metacomet’s coalition began fleeing. In April, Canonchet, the Narragansett war leader, was captured in a surprise attack. Offered amnesty in exchange for a peace agreement, Canonchet refused. When told he would be executed, Canonchet replied, “I like it well. I shall die before my heart is soft, and before I have spoken a word unworthy of myself.”

By mid-summer, 400 insurgents had surrendered. They were likely enslaved to local households or deported to the Caribbean and beyond as punishment, if not tortured and executed. As the war shifted in the colonists’ favor, the governing council of Charlestown, Massachusetts called for “a day of Solemn Thanksgiving and praise to God” on June 20. “It certainly bespeaks our positive Thankfulness,” the town proclamation read, “when our Enemies are in any measure disappointed or destroyed.” Salem minister Increase Mather10 agreed, adding, “We are under deep engagement to make his praise glorious; considering how wonderfully he hath restrained and checked the insolency of the Heathen. That Victory which God gave to our Army, December 19. and again May 1811 is never to be forgotten.”

A colonial map of New England from 1677.

The United Colonies of New England were beginning to coordinate themselves better, too. Founded as a confederation including the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, New Haven, and Plymouth in the 1640s, the UC hoped to guard against Native Americans and the Dutch, preserve a rigid form of Puritanism, and capture and return runaway servants. The Pequot War five years earlier had made this first point particularly pressing. Each colony sent two delegates to an annual convention at which six votes were required to ratify agreements. Unresolved matters were sent back to each colony’s legislature to be decided independently. Rhode Island was not allowed membership in the coalition, even during Metacomet’s War, because of its stance on “religious freedom” (as the residents subscribed to a different form of British Puritanism). Throughout the war, the United Colonies managed to raise an inter-colonial force of 1000 troops. Yet even at its best, the UC was rife with divisions; it disbanded soon after the conflict.

Divide-and-conquer tactics eventually won the day. Benjamin Church, a leader of the forerunner of the US Army Rangers, understood that European-style, frontal attacks would not conclude the war. Instead, Church recruited Native Americans (mostly Praying Indians) to fight and teach Native tactics and strategy, fielding smaller, more flexible units familiar with the environment and able to blend in with the land. At the outset, colonial militiamen did not trust their Native allies, believing that “they were cowards [who] skulked behind trees in fight,” and that they intentionally “shot over the enemies’ heads.” Certainly some reports of Native conscripts who after making “shew of going first into the swamp they comonly give the Indians noatis how to escape the English” must have been true. But after a year of combat, Church had whittled his Native troops down into a trusted core. In August 1676, Church led a party into Metacomet’s Assowamset stronghold, where Praying Indian John Alderman killed Metacomet.

As Metacomet’s body was pulled from the muddy swamp, Church beheld him, remarking how in death he looked like a “doleful, great, naked, dirty beast.” Church declared, “Forasmuch as he has caused many an Englishman’s body to be unburied, and to rot above ground, not one of his bones should be buried.” As a show of honor, Church awarded Alderman with Metacomet’s head and right hand, burned and scarred from firing pistols. Next, Church set aside his left hand for Boston, a trophy for their victory, while the rest of Metacomet was quartered and hung from the trees of Miery Swamp.12

Returning east, Alderman sold Metacomet’s head to Plymouth authorities for 30 shillings, the standard colonial price for Native heads during the war. For the rest of his life, he would display the insurgent’s hand for a fee.

As chance would have it, Metacomet’s head arrived in Plymouth the day of a colony-wide Thanksgiving. One can imagine the elation the colonists felt, checked by their religious instructions to restrain excessive merriment. Some colonists concluded that god had made the proper choice in picking a Native American to kill Metacomet, so Puritans might not be made too proud. For the next twenty years, the entrance to Plymouth was decorated with Metacomet’s impaled head—a lesson to any who might stand in the colonies’ way, but also an unintentional reminder of life outside of the colonies.

The violence of the map.

If the war was horrible for the British, it was catastrophic for Native Americans. Roughly 6000 died during the war, while hundreds of others were taken captive. Metacomet’s wife, Wootonekanuske, and his nine-year-old son,13 his only immediate family to survive the war, were enslaved and sent to Bermuda. Disease returned, too, “it being no unusual thing for those that traverse the woods to find dead Indians up and down, whom either Famine, or sickness, hath caused to dy, and there hath been none to bury them.”

Colonial officials hanged, shot, and decapitated dozens of Native prisoners, if not hundreds. Hundreds more were indentured or enslaved throughout New England or deported as slaves to as far away as Morocco. Weetamoo drowned while fleeing colonial troops, who then placed her head on display in Taunton, Massachusetts. In the coming months, as settlers brought Native prisoners through town, many screamed and wept at the sight of Weetamoo’s impaled head. Tantamous and his family were hunted down too. In the summer of 1676, he and other rebel leaders—Sagamore Sam, Netaump (One Eyed John), and Maliompe—were taken to be hanged at Boston Commons. Yet the spark was not yet extinguished: as his captors paraded Tantamous through the streets with a noose around his neck, the 96-year-old still “threatened to burn [Boston] at his pleasure.”

Those who could flee north and west did, blending into refugee villages or being adopted into formal tribes. Many surviving members of the Wôpanâak joined the Alnôbak (Abenaki) in Quebec, Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, continuing the fight against colonization. Over the following eighty years, the Alnôbak, along with other members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, fought five successful wars against Massachusetts’ attempts to expand into their homeland.

Wamsutta Frank James giving the speech that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had attempted to suppress at the base of the statue of Metacomet’s father, Massasoit Ousamequin, in Plymouth in 1970.

Afterwards

After Metacomet’s War, Native Americans who had been enslaved throughout the Western world persevered and continued to resist in a variety of ways. Today, descendants of the Narragansett, Wôpanâak, Podunks, Nipmucs, and other peoples still live throughout New England, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and beyond.

The colonists had suffered thousands of casualties. The villages and economies of Rhode Island and Massachusetts lay in ruins; the frontiers of Plymouth and Massachusetts had been pushed back to just twenty miles west of Boston. It would take a generation or more to rebuild. Taxes remained sky-high over the following decade to pay the debts of the war. Yet the settlers continued to advance, slowly turning Native homes and hunting grounds into farms and raising a church atop of Montaup’s ruins. Today, the former Narragansett capital is owned by Brown University.

In unifying to massacre Native people and steal their land, the colonies had shifted from functioning as distinct, scattered settlements to acting as a unified front in an expanding colonial project. Class tensions, too—between servants and masters, wives and husbands, the deviant and the pious—were set aside for the sake of settler unity. Britain itself had done little to support the colonies during the war. In acting independently, the colonists set the foundations for the beginnings of a shared New England settler identity. The war with the Wôpanâak and their allies foreshadowed the French-Indian War, which set the stage for the Revolutionary War against Britain. In the history of the Americas, “independence” has always been entangled with colonial violence.

Without these genocidal wars—and the transatlantic extraction economy, patriarchal hierarchies, and duplicitous Christian moralism that gave rise to them—there never would have been a New England or an American Revolution. This is the legacy Donald Trump invokes when he calls on his supporters to “make America great again.” It is the legacy his Democrat rivals are leveraging when they talk about “building back better” according to a more inclusive vision of America. It is the pattern of destroying Indigenous communities and ecosystems in order to reorganize the survivors according to the logic of colonialism. America, founded on genocide, slavery, and stolen land.

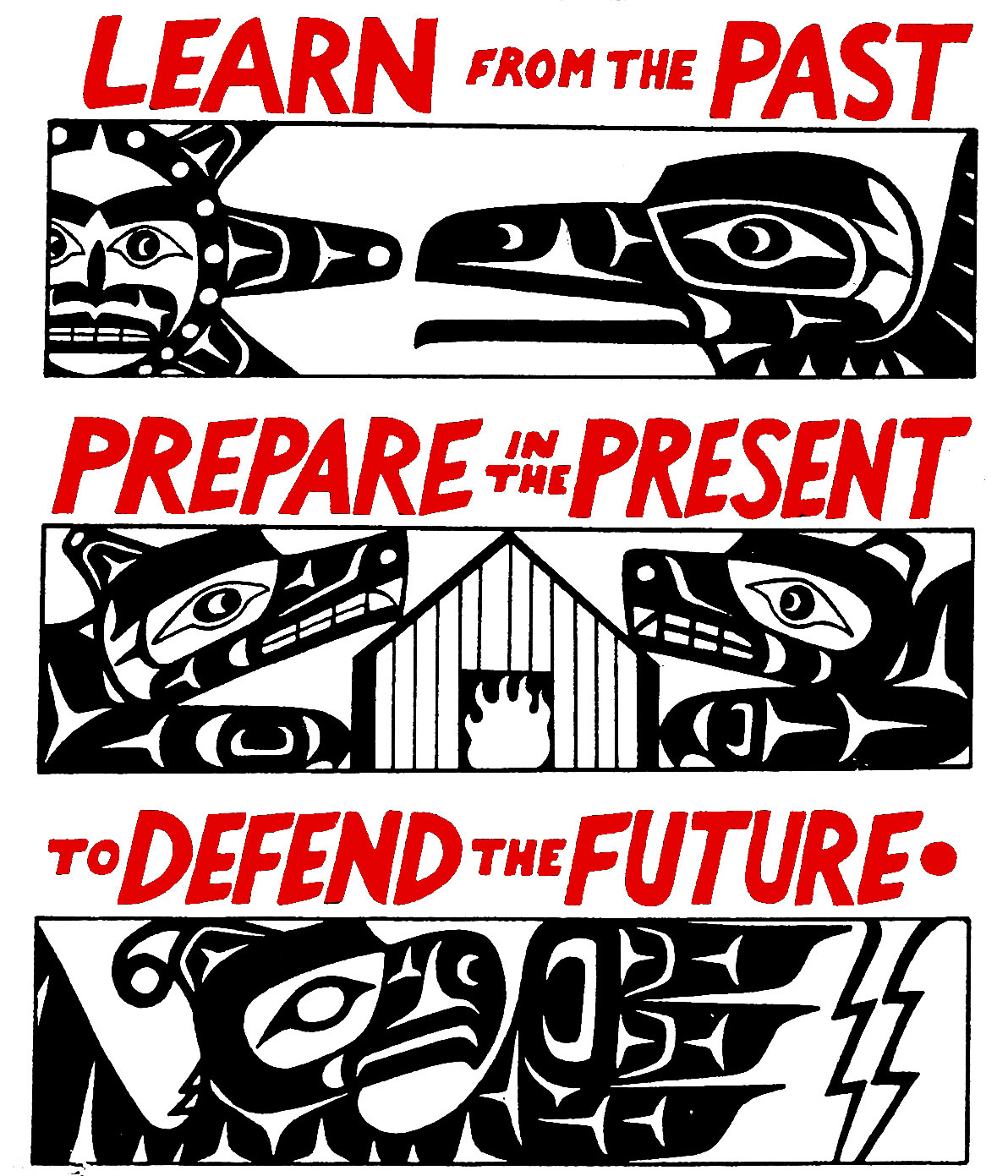

Artwork by Indigenous anarchist and artist Gord Hill. We recommend his book 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance and his website Warrior Publications as points of departure to learn more about historic and current Indigenous struggles.

-

The Mayflower passengers chose to settle in one of the ghost towns of the Patuxet, recently emptied by the plague; the fields were still fertilized and tilled. They were hardly ignorant beneficiaries of the plague: Plymouth’s charter explicitly referenced “a wonderful plague amongst the savages there heretofore inhabiting, in a manner to the utter destruction, devastation, and depopulation of that whole territory.” The pilgrims took it as a sign from God that the land “should be possessed and enjoyed by such of our subjects and people.” Miles Standish The Puritan Captain, John S. C. Abbott, page 110. ↩

-

The feasting aspect of this 1637 Thanksgiving is noteworthy, as Puritans liked to think of themselves as ascetics. ↩

-

Roger Williams had founded the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations five years earlier. He is remembered today as a man persecuted by the rigid Puritans of Massachusetts and a champion of religious freedom. This view omits his white supremacist attitudes and role in Native genocide. During the Pequot War, Williams advised Winthrop to “deale with them [Native Americans] wisely as with woules [wolves] with mens braines.” John Winthrop’s World: History as a Story, the Story as History, by James G. Moseley, page 78. ↩

-

This statement is profound. How often do those deemed less by those in power contribute to and shape the world, for better or worse, only to see their contributions ignored or taken for granted? Without Ousamequin’s intervention—teaching the settlers how to plant and grow regional food, navigate local customs, and survive their first winters—Plymouth would certainly have perished. While this might have been for the best, Metacomet is right to say the settlers were his father’s children—that he was one of many sources, one of many parents. Yet the colonists, like many of their heirs, trace their ancestry selectively, choosing the most patriarchal accounts of the past, the most whitewashed versions of their origins. ↩

-

By this time, the Pequot had reconstituted themselves, though much more in line with British values than before the Pequot War. As a consequence of the war, the middle-aged generation of the Pequot had been enslaved to settler households since childhood, and the younger generation had lived almost entirely within the colonists’ world. ↩

-

The United Colonies of New England was one of the first official attempts to coordinate the colonies of New England. ↩

-

The testimony that Joshua had willingly joined the Narragansett should be viewed with some skepticism too. In order to be found guilty of High Treason, it was necessary for two eyewitnesses to give corroborating testimony. In Joshua’s case, one eyewitness gave testimony about the scalp he provided the Narragansett, while another described his rallying demoralized Narragansett fighters. We can’t know whether these witnesses might have been pressured into falsifying their testimony. ↩

-

Women convicted of High Treason were to be burnt at the stake. The Proceedings of the First General Assembly of “The Incorporation of Providence Plantations”, William R. Staples, page 22. ↩

-

Brought to you by the freethinkers of colonial Rhode Island. ↩

-

Increase Mather was a Puritan minister, a Massachusetts Bay Colony official of considerable importance, the father of Reverend Cotton Mather, and a President of Harvard. ↩

-

On December 19, colonists massacred between 300 and 1000 Narragansett in the Great Swamp; on May 18, they killed 100 sleeping Nipmuc in the village of Peskeompscut and drowned 130 more in the nearby Connecticut River. The slaughtered Nipmuc were mostly non-combatant women, children, and elders. ↩

-

For decades afterwards, visitors to Miery Swamp claimed to see parts of Metacomet still hanging from the trees. While his remains likely didn’t last that long, such sightings indicate something of the psychogeography of New England following Metacomet’s War. ↩

-

Apparently, the clergy of New England debated the fate of this nine year old at great length. After a year of consulting scripture, they decided not to hang him, out of mercy, but instead to deport him as a slave. ↩